How Stolen Jewish Loot Arrived in Nazi and American Control

Joseph Pool

INTRODUCTION

As World War II raged on, the Nazi Regime and all of its monstrous machinations spread like a dark cloud across Europe. In its wake, it brought about destruction and devastation to the history and lives of people across the continent. Through their twisted philosophy of eugenics and cultural superiority, they justified their reign of terror and the seizure of valuables and significant artifacts from those that had been caught under their control. While many individual artifacts were stolen and offered to the Reich or their highest bidders, another haunting example exists in the way the Nazis gathered and transported many artifacts across their occupied territory. This logistical locomotion manifested itself in the Hungarian Gold Train, a Nazi-operated train which transported much of the stolen gold, gems, paintings, rugs, and valuables away from the encroaching Allied forces (Zweig 2003). When it was eventually captured by American soldiers, however, they took the loot for themselves—selling and giving these stolen family and community heirlooms to family, friends, and those willing to pay the right price.

From Nazi hands to American soldiers’ grasp, the stolen loot and art of European Jews and other groups made its way across the continent and eventually, the world. With it came the challenge of how to again locate these heirlooms, the question of if and how they should be returned to their origins, and who should bear the burden for this ordeal. While the American government has recently acquiesced to political and legal pressure (NBC 2005) and began the process of repatriating the valuables, there is still much work to be done and many questions to be asked. This paper will seek to explore the case of the Hungarian Gold Train and determine the practical and ethical dilemmas facing its resolution. Moreover, it will use these considerations in order to recommend a course of action to be taken by all of the relevant stakeholders.

THE HISTORY OF THE TRAIN

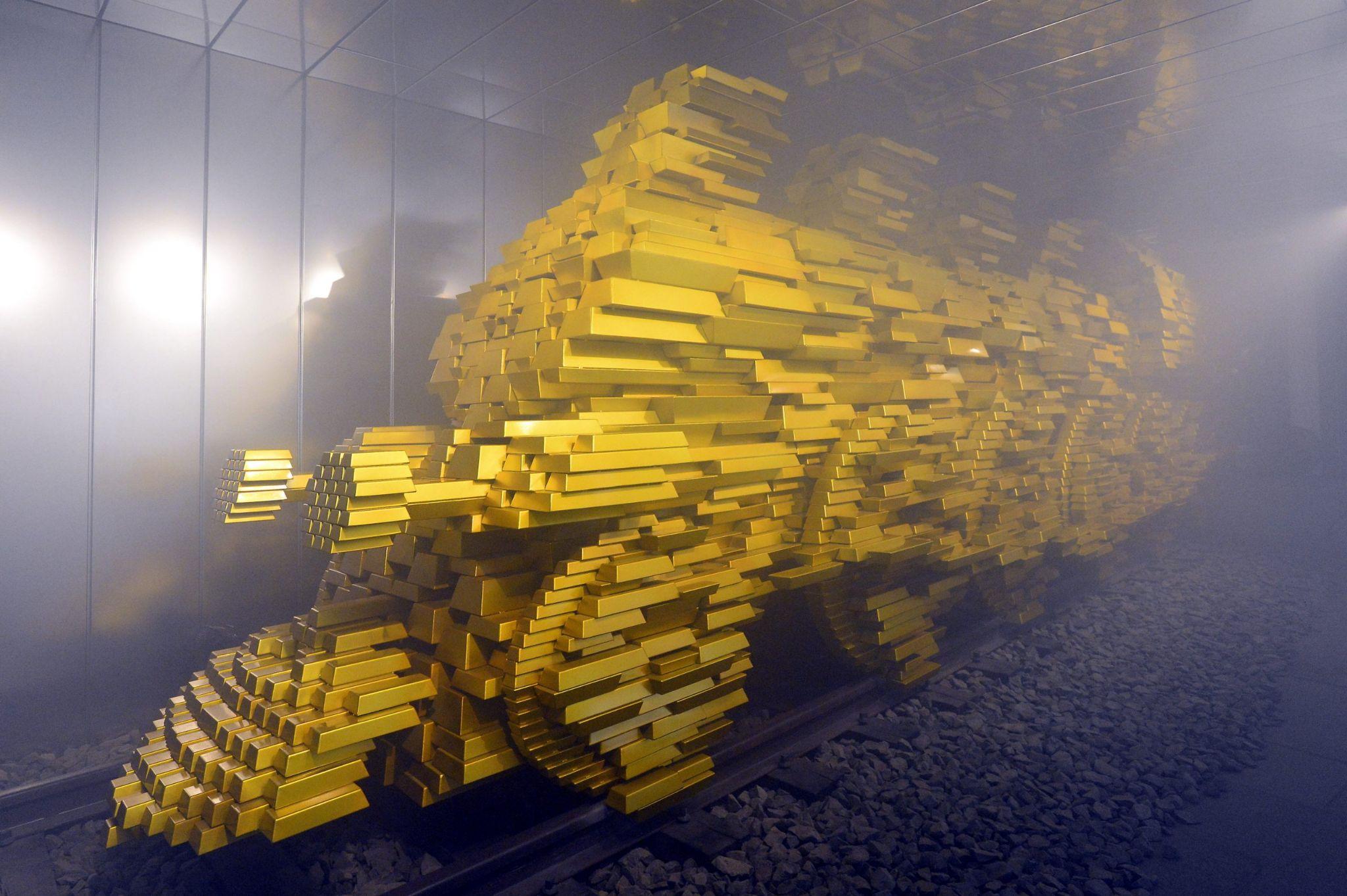

46 cars long and filled to capacity with over $4 billion of stolen loot (source forthcoming), this train was central to the Nazis campaign of ensuring artistic and cultural supremacy. More than a relic of the Nazi reign, the Hungarian Gold Train has become a part of pop-culture and occult legend. Conspiracy theories about a different Nazi gold train led to a decades-long, expensive hunt through rivers and mountains to find an elusive—and nonexistent—bunker housing a myriad more of stolen art and valuables. To this day and despite evidence to the contrary, some people assert that this train and bunker exist, hiding some of history’s most priceless artifacts (Lewis 2015). The real Hungarian Gold Train was featured heavily in the second season of the Netflix show, Russian Doll (St. Claire 2022), and alongside the supposed Nazi Gold Train, partially inspired the recent Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, both of which feature a Nazi train carrying stolen valuables and priceless artifacts away from the battle front as the war began turning against the Germans. These chart-topping pieces of media demonstrate the curiosity generated by Nazi occultism and mythos. Other shows, such as Babylon Berlin have also starred the transportation of gold by Nazis and showcased the deliberate use of trains to aid in their movement of stolen artifacts and items beneficial to the Nazi cause. With the trains, both real and fake, legitimate academic and professional interest was garnered in sorting fact from faction and attempting to locate the loot As seen below, the train has become such a mainstay in discussion of the era that even the Hungarian Money Museum has erected a monument to commemorate the role it played in their history, as well as in the history of stolen cultures.

Commemorative art installation at the Hungarian Money Museum.

As explained by Anne Rothfeld of the National Archives, the looting of art was crucial to the permeation of Nazi ideals within their territory. She explains, “Art looting that had begun on an ideological basis became an organized government policy. For Nazi officers seeking social status and promotion within the party, collecting and giving art confirmed one’s dedication to promoting Nazi racial ideologies in the Reich” (Rothfeld 2002). This practice was so prolific that over 650,000 pieces were looted and brought to the Nazi cause. Some estimate that as many as a fifth of all European art was seized and under Nazi control. In fact, this art looting left such an impact that a special term was created for it: Raubkunst.

The theft of this art was a feat of immense logistical operation. It worked via many channels and relied on officials using their power to extract the valuables from others. In many cases, searches were conducted in Jewish households, as well as other “undesirable” groups, and contraband, including this perceived inferior art was taken and sent to Nazi storehouses and exhibits. Another method through which this was conducted was by exacting a tax on those seeking to leave Nazi occupied territory. This “flight tax,” known as the Reichsfluchtsteuer, rose beyond 25% of a person’s assets and provided legal ground for officials to seize the art and valuables of Jewish families. It was widely used and brought the Reich much of the art they were after. In combination with other forms of illegal searches and organized looting, this tax played a major role in the Nazi campaign toward cultural hegemony.

For the Nazis, the seizure of art was a necessary step in the process of securing the permanence of Nazi culture and the transformation of Berlin into a hub of the arts and a superior culture. This was not a war of race or politics, it was one in which the Germans hoped to achieve dominance over culture and lifestyle. By fostering a network of art theft and subsequent relocation, they were hand selecting what would and would not meet their criteria as things of value. The items they extolled would be placed in museums for all under German control to see. The ones viewed as lesser would either be stowed away or shown in exhibits of degenerate art. The Hungarian train, along with many others under Nazi operation, helped to actualize this idea and put the Reich on the tracks of cultural conquest.

The collection of “degenerate” art stolen from European Jews by the Nazis was put on display and frequented by top Nazi officials including Hitler and as pictured above, Joseph Goebbels.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE ART

For those under occupation, as well as people in general, art plays a significant role in capturing and evoking feelings and memories. Loot, heirlooms, and paintings alike allowed people to connect with their past—both familial and cultural. As such, it goes without saying that by stripping families of their artifacts and heritage through the flight tax and blatant theft, the Nazi Regime was ripping apart connections to the past and one another. The categorization of Jewish art as degenerate furthered this divide, and the placement of these pieces onto the trains to be shipped away only solidified the permanence of this damage. Some of this art and some of these valuables had been passed down through generations and served as a living lineage for these families and communities. In the ensuing fight to return the art to its rightful owners, care must be paid to ensuring some form of resolution that seeks to remedy this damage.

THE FIGHT FOR THE CARGO

This case is more than a legal one of property rights and international law, it is one that could and should be examined through the lens of ethics. Different sides have relied on philosophies of law and theories of ethics to justify their claim to the cargo. Without fully analyzing and scrutinizing these, one can not hope to arrive at a reasonable, moral conclusion of who should assume ownership of the pieces and compensation from the era of the Gold Train. This section seeks to explore various ethical theories in favor of and opposed to the repatriation of art and providing remedy to the families and individuals harmed by the theft.

Those defending the American claim to the Nazi loot are relying on a pragmatic ethical framework. Focusing on the practical instead of the philosophical, they may argue that the art would be too hard to regather and return to its various owners. These political and ethical realists would decidedly claim that the Americans won the war, have the power, and thus have no need to give back what was claimed as their own. These realists would insist that for better or worse, might makes right and that as the Germans were the dominant force and claimed the art, so too can the Americans following their victory. These “might makes right” ethicists would agree that spoils of war go to the victor and would attempt to paint these items as spoils of war. In normal war circumstances, this is often the truth: winners get to divide the spoils of the losers as they please. International rules of engagement often lend to this and allow for some of the seizures. However, the situation of stolen art and the use of the trains was a different story. Legally, these pieces were not Nazi property nor spoils of war, they were the stolen artifacts of civilians and thus, can not reasonably be held to the same standard. Moreover, the argument that might makes right can be shown as possibly justifying the Nazi theft in the first place, something many arguing for this opinion would not want to associate themselves with.

Another group in favor of allowing America to keep the pieces are those simply too lazy to do the work incumbent upon them in solving this situation. People in this group may cite the fact that to return the art, they would need to locate and contact the families of those who once owned it, a feat that would prove extremely difficult given that many have since passed away or changed their names following the War. They would go to great lengths to paint this obstacle as insurmountable and try to reason that so much time has passed since the theft by Nazis and Americans that there is no real reason to even carry on with repatriation efforts. It should go without saying that this argument is inherently flawed and lacks any semblance of compassion toward the victims and their families. Moreover, this same flawed logic could apply to anything that appears mildly inconvenient, and should not be considered an ethical argument in the first place as it prioritizes ease of task over morality.

Cosmopolitanists—those believing that everyone in the world is part of one human culture and that art should be shared across borders and groups—may argue against repatriation for a different reason. They would acknowledge that the art should not have been stolen and that what the Nazis and soldiers did to the objects and lives of others is reprehensible. As we are all part of one human race and society, the devaluing of the lives and remnants of others is considered by cosmopolitanists to be morally wrong. Their argument instead would revolve around the purpose of art and the practicality of its current location. They may claim that if placed inside American museums or exhibits, the art can continue to tell the story of its owners and their cultures while being accessible to more people and remaining protected. Instead of having art hidden away in some family’s home, the most people could gain the most appreciation from its public protection and presentation.

In favor of repatriation would be those who follow Kantian ethics and ideas of an unwavering, uncompromisable moral duty incumbent upon all rational people. Kant and his followers would likely classify the correcting of an egregious wrong to be a moral imperative. This imperative would be seen as something that must be followed no matter the circumstances, and would naturally be applied to the case of repatriating art. If lying and stealing are always wrong, allowing them to continue on by not acting would be seen as just as wrong. Kantians would demand an ethical solution be reached and the valuables be returned to their initial owners. Additionally, they may even go a step further and ask for recompensation or restitution for the damages caused by the lying and theft.

One final ethical argument in favor of returning the art is that of Aristotle’s virtue ethics. This belief argues that the goal of a person is to live a good, moral life as a member of a good, moral society. To achieve this, one must align their action with the practice of virtues—concepts such as bravery and humility—and avoid a life with any virtue in excess or deficiency. Virtue ethicists would preach the need for virtues of justice and kindness to be utilized in returning art to their rightful owners and addressing these historic wrongs. They would insist that in order to practice ethics and foster a good society, an individual must be willing to fight injustice in the form of continued theft and withholding of valuables and heirlooms. They would have seen the Nazi actions as completely out of line with virtue ethics, and would also condemn the American soldiers for continuing this dark trajectory through their seizing of the Hungarian Gold Train and the looting of the Nazi train system and the nations in its wake.

CONCLUSION

Billions of dollars in looted value and millions of lost lives was the cost of the Nazi campaign to become a cross-continental, culturally-hegemonic colossus. Within this ideological effort was a movement to make the Reich the centerpiece of world affairs and the arts. This desire brought forth a complex plan to seize art and artifacts from their owners and centralize them all under the Reich’s control. A collection of trains—notably the Hungarian Gold Train—provided the Nazis with the logistical capabilities to move priceless heirlooms and cultural artifacts from their rightful custodians to Hitler and his henchmen. When these trains were seized, the art was taken by American soldiers and distributed further across the United States. While possibly considered spoils of war due to their time in Nazi custody, these artifacts had rightful owners and should have been repatriated. Despite countless court battles and admissions of guilt from the government, this process is just getting started. While the legal battle rages on, the ethical answer to the case of the Hungarian Gold Train has existed since the beginning of the dispute: the stolen artifacts must be returned to their owners and their next of kin. The possessions of the Hungarian people and European Jews should never have landed in Nazi or American hands, and the longer it takes to return them, the more complex it will become.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“United States settles World War II-era Hungarian Gold Train claims.” The American Journal of International Law 100, no. 1: 220-22. https://doi.org/10.2307/3518845

BBC News. 2015. “Nazi Gold Train ‘found in Poland’.” https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-33994483

Berman, Steve. 2005. “Hungarian Gold Train.” Hagens Berman. https://www.hbsslaw.com/cases/hungarian-gold-train

Lewis, Danny. 2015. “Sorry, treasure hunters: That legendary Nazi Gold Train is a total bust.” Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/sorry-treasure-hunters-legendary-nazi-gold-train-total-bust-180957573/

NBC News. 2005. “U.S. apologizes for WWII Gold Train case.” https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna9662733

Rothfeld, Anne. “Nazi Looted Art.” National Archives and Records Administration, 2002. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2002/summer/nazi-looted-art-1

St. Claire, Joshua. 2022. “The Hungarian Gold Train From Russian Doll was a real Nazi train.” MensHealth. https://www.menshealth.com/entertainment/a39760853/russian-doll-gold-train/

Tiefer, Charles, Jonathan Cuneo, and Annie Reiner. 2012. “Could this train make it through: The law and strategy of the Gold Train Case.” University of Baltimore School of Law. https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac/547/

Zweig, Ronald. 2003. The Gold Train: The destruction of the Jews and the looting of Hungary. New York: Harper Perennial.