Joseph Pool

ABSTRACT

In the ancient Roman world, food was more than mere nutrients. Food, and the invitation to partake in it, was a potent form of political currency used to lobby for favor or garner support from those at, above, or below one’s perceived social status. The price of these otherwise free meals was the expectation of political and social submission to and support for the host. Private dinners were sponsored by patrons looking to cultivate dependency and loyalty from their guests. On the other hand, public feasts were used by emperors and elites to display their power to the public in the hopes of maintaining and gaining respect and reverence.

INTRODUCTION

With the Mediterranean region having a crop failure rate of over 20%, food was not always a guarantee for small-scale farmers and families. They found a solution in voluntary yet necessary arrangements with more powerful landowners, creating a relationship of a client and a patron. The client was given land on which to farm and provided with equipment and tools otherwise unavailable to them.[1] In exchange, these patrons would ask for the help of their clients in securing political, military, or economic victories; they needed clients to help further a path for the patron to grow their power and prestige.[2] The clients meanwhile would have safeguards and provisions against famine, and protection from others who might wish them harm. The need for food inspired this relationship, and the tool that maintained the patron-client balance was the opportunity for each to engage in shared meals with the other.

For the local landowners and officials who had their heart set on public office or more prominence, the guestlist they curated for a nightly dinner party had the potential to make or break their aspirations. Their assigning of seats and designing of entertainment served as a way for the patron host to demonstrate their capabilities and access to connections. The best patrons were themselves invited to the meals of those in higher circles, granting them access to resources and power that they could pass down to their clients.

Those at the apogee of their careers may even be invited to participate in a public banquet hosted by the Emperor himself. Far removed from the private dining room hidden within a home’s private quarters, these lavish banquets were put on display—intentionally designed to showcase the political elites and power players to the masses of spectators.[3] While public and private dining had different venues, guest arrangements, and roles for the host to play, these meals shared a common intention: to allow hosts and guests alike to leverage their meal invitation for political and social benefit. Through an analysis of ancient and modern texts as well as archeological evidence, this paper will compare and contrast the purpose of private dinners and public feasts. In doing so, it will define the political purpose of free food in ancient Rome.

CLIENT SYSTEM

In antiquity, Roman society operated on a binary of haves and havenots, patricians and plebeians, or patrons and their clients.[4] The goal of these patrons was to use their wealth, influence, and connections in the way that best grew their power and prestige. This could take the form of allegedly altruistic donations to their cities, or bribes paid to city and Roman officials. Notably, the patron’s connections and resources had the possibility to help their clients and in turn, garner continued allegiance and support. Clients wielded considerable soft power; they made up the masses and through their labor and dedication, had the ability to help patrons rise or ensure their fall. On the other hand, without the support of a patron, the client was likely to financially and physically starve if any drought or inconvenience arose.[5] As a result, this precarious balance of haves and havenots encouraged mutual aid and reciprocal responsibility amongst the social castes. The food provided by local elites and leadership was paramount to the proliferation of the patron-client system, and was key in establishing those who would eventually rule. As expressed by historian Greg Woolf, “Food gifts symbolised the patron’s role as provider for his clients.”[6]

PRIVATE DINING

Business Breakfast

The daily life of a Roman citizen was centered around food, and the search for sustenance. Not always a guarantee, the prospect of a meal allowed for patron-client relationships to be reinforced and to flourish throughout ancient Roman society. The day of a Roman was centered around the patronage system, and their decisions throughout it were aimed at utilizing their patron to gain food and favor. To provide for one’s family and dependants, clients were in constant search of invitations to eat, and opportunities to have enough food that they could provide for those reliant on them.[7]

The day started at the salutatio matutina—a casual business meeting held over an assortment of breads, fruits, nuts, and olives.[8] This slice of the day was set aside for clients and patrons to have one-on-one meetings in which they could communicate their needs and wants to one another. Food served as an incentive for clients to attend these meetings, and to begin their day by providing updates and thoughts to their patrons. Often, urban clients would sell their leftover food from the salutatio out in the city in order to exchange it for other goods and services. By paying homage to one’s patron, a client received tangible benefits—both socially and monetarily. By caring about their client’s concerns, a patron secured continued loyalty and created food-based dependency.

This business breakfast permeated through all tiers of Roman society. Patrons themselves were typically clients to another patron. As their own clients had done with them, these patrons attended meetings in which they were the ones requesting assistance and receiving sustenance. These breakfasts were key to networking and allowed for those sponsoring to stay politically and socially aware of pressing issues and general anxieties. The needs of clients that could not be met by their patron could possibly find solutions in the patron’s patron. Conversely, a work request from a patron could be taken care of by his or her client. The salutatio provided a mutualistic, albeit short exchange over a light meal, and it provided food to the clients in attendance. It also engendered the possibility of those clients being connected with others, and if Fortuna was on their side, of receiving an invitation to dinner. If by the end of their meeting, however, the client did not receive an invitation to dine with their patron, the rest of their day was spent in pursuit of an invitation from anyone else.

Following their morning meeting and light bites, the urban clients and patrons went to work in the city. Their late mornings and early afternoons were spent fulfilling their tasks of the day while they attempted to secure an invitation to dinner.[9] In the streets, taverns, and markets, people were able to talk with those they knew and possibly exchange items and invites. With the prospect of food in mind, people sought to turn strangers into acquaintances, and win the favor of someone hosting dinner. Resources and insider information may have been offered to this end.

Between work and this search, people expended energy that needed to be replenished before evening. Thankfully, cities bustled with street side vendors providing everything from pastries and snacks to fish and fruit. If those were not filling enough, thermopolium dotted streets and provided quick, hot meals to those who had some extra money—perhaps from previously selling their salutatio leftovers. The combination of vendors, taverns, and fast food counters provided much of the Roman working world with food during the day.[10] They also created networking opportunities and proved to be popular gathering spots for gossip, deals, and invitations to be exchanged. If dinner plans had not been secured by this point, there was one last opportunity to impress a patron enough that one could receive an invitation to their dining table; those searching for food needed to make a good impression at the bathhouses.

These bathhouses were the place of casual politics and conversations. In these complexes, food could be purchased, massages and workouts could be undertaken, and the citizens in attendance had a chance to mingle with one another and discuss their views on the issues of the day. If someone brought up intellectually interesting points or presented a humorous perspective, they would often be extended an invite to that evening’s dinner from someone with a seat to spare. As extolled by Roman virtues, those who conducted themselves well in the public sphere—whether the forum or the bathhouse—were deserving of praise and opportunities. For the price of providing dinner, a patron could potentially secure a rising political star, or secure an alliance with the powers that be. For those interested in pursuing politics at a more prominent level, this search for new or newly-available talent was a non-negotiable part of daily life. Whether at the morning salutatio with their clients, the afternoons with friends at taverns, or the evenings spent in the bathhouses, a commitment to filling their trimalchio’s couches was the goal around which most local elites oriented their days. By virtue of the people in attendance, the elite would either be maintaining existing relationships or making strides to cultivate new ones.[11]

From Atrium to Triclinium

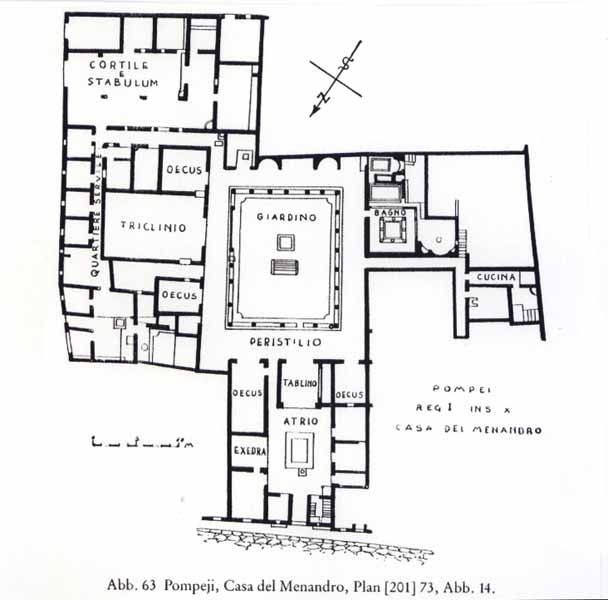

Cementing the emphasis on how social class was determined through meals and despite widespread food insecurity, the coveted dinner itself was more about the guests than the menu. Those with invitations knew the importance of their company. As captured by John Wilkins and Shaun Hill, “Stern disregard of what is set before you and ostentatious regard for nuances of taste and provenance of the food to be eaten are each attitudes meant to send a message … The fraternity of those dining is the core issue and not the menu.”[12] Those lucky or connected enough to have secured one of the nine seats in the dining room were aware of the gravitas their invitation held. The patron was choosing them—whether a patrician of similar status, a significant guest that was to be praised, or a client who had gained special favor—to take part in a meal that touched on all senses and allowed the patron to prove his or her character, knowledge, and capabilities. This all began the moment guests stepped foot into the host’s home, seen in the floor plan below.

A floor plan from Casa del Menandro showing how those looking to enter the triclinium would have to be guided from the publicly-accessible atrium in the front of the house across the private threshold defined by the peristyle.

The dining experience, and thus the host’s living proof of social class, began from the entrance of the home. Operating on a vertical axis, the entrance was directly facing a reflecting pool, fountain, statue, or other feature of wealth and caliber. On their way to the dining room, guests would be guided through the various collectibles and treasures on display—informing them of their host’s personal narrative and subtly reinforcing why the host is the one in power. The second significant step occurred when guests crossed a threshold by passing through the private peristyle. This signified a departure from publicly-accessible space and an entry into the host’s good graces and personal care. By crossing the threshold and with the promise of an elaborate meal, the guest was yielding control of their decisions and time to the host and whatever he or she had planned.

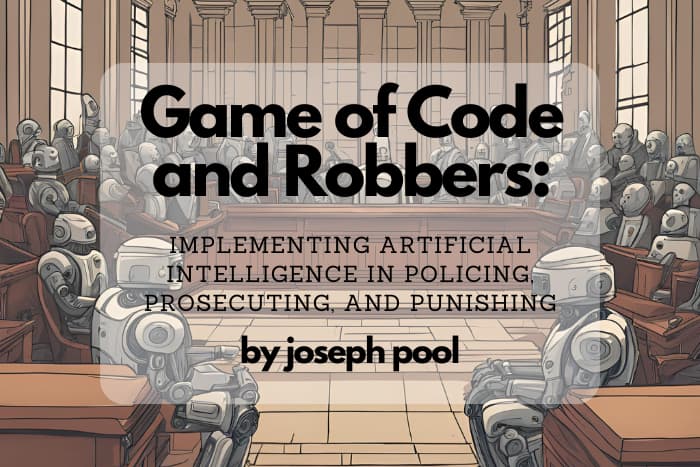

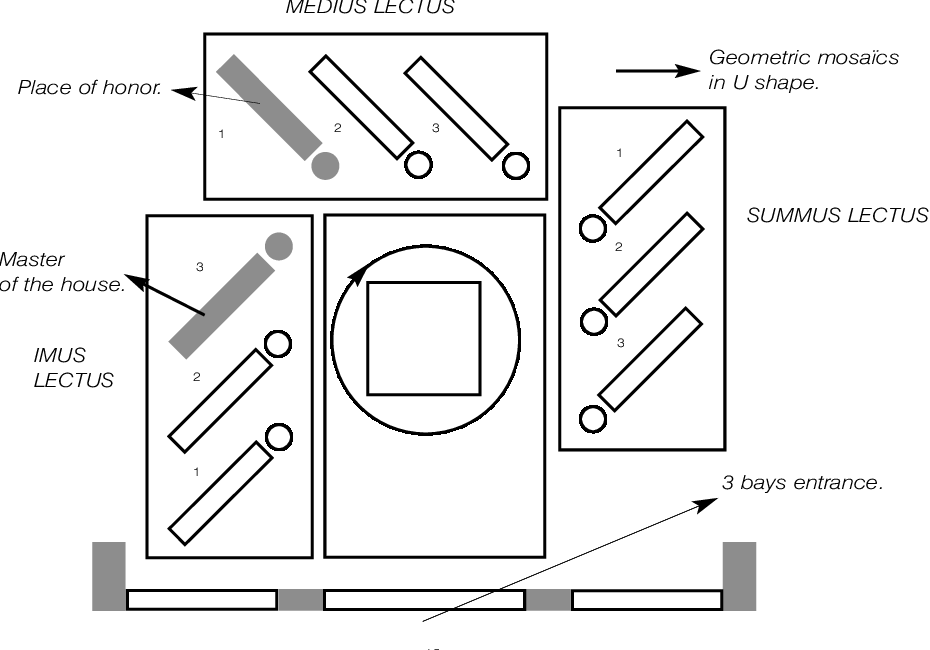

Before the meal began, the host had another way of defining the power structure of the guests: the assigned seating. Roman triclinium were set up with three couches of three seats, all oriented around a central table.[13] Due to the arrangement of couches and the fact that Romans reclined to one side as they ate, your seat determined who you would be able to converse with at the meal, and how close you would be to the host and high caliber guests. The host and guest or guests of prestige would sit near each other in a central place. This allowed for deals to be made and for an ingroup to form, even in the already exclusive dining room. To be placed in these better seats was a sign of great respect and demanded reciprocity in thought and action. Explained by Dunbabin, “There would be even more emphasis in these rooms on hierarchical seating arrangements: the central couch will inevitably have greater prestige and must have accommodated the guests of honour, whereas those at the far ends are very remote from the centre.”[14] This couch arrangement is pictured below.

Labeled triclinium seating chart showing where the host, guest of honor, and other guests would sit. Arrows also show the entrances and the wall decor that would accompany certain seats.

Even before food was brought out, people knew their place, both at the table and in the eyes of the host. The place settings sent a message to all in attendance: what their current status was amongst the group, and who they had to impress to climb higher. For any host attempting to improve their socio-political standing, they needed to play a balancing game between placing themselves in the spot of honor and yielding it to one who could open more doors and allow them to move up in society. If, for example, the host was planning to run for office and needed support, a popular fellow patron might be worth honoring and giving the first seat to.[15]

Dealings Around Dinner

For Romans seeking to impress their guests, dinner was an experience far beyond the food. From murals depicting a forbidden, naked Diana to multi-paneled epics taken from Greek and Roman myths,[16] the art was curated to convince the guests of the host’s power. Moreover, the host was presented with a unique ability to display either their expertise of history and myth to the entire dinner party, or to gain points with the inner circle by ridiculing those in lower seats who did not know the true stories. As seen in the house of Octavius Quartio, “Analysis of the content and composition of the friezes proves that, like the Dionysiac frieze of the Villa of the Mysteries, they were tailor-made for this room. The design cues the viewer repeatedly as he or she moves through the space to follow the narrative thread.”[17] This series is pictured below.

Remnants of friezes that would have been on display in the triclinium of Ocravius Quartio. There are two sets of images that would show different panels depending on a guest’s seat and therefore view.

By leading the party into the room, the host could guide them through the chronological order of ancient myths. Meanwhile, by placing guests in specific seats, he could ascribe to them the characteristics of that part of the story—whether a hero’s ascension to godhood or the death of a loved one. In presenting themselves as the leader of the meal and the expert on philosophy, history, and art, hosts were vying for favor in the eyes of peers and clients alike.

This carefully-curated act carried over to the spectacle performed by hosts as food started to flow forth from the kitchen. Recalling a scheme from the fictional feast of Trimalchio, Christopher Jones notes, “Before [the boar] is carried in, the servants put up tapestries depicting nets and all the paraphernalia of hunting; then Spartan hunting dogs bound among the tables; finally the creature itself is brought in, with little baskets (sportellae) filled with dates hanging from its tusks. The carver is dressed as a huntsman.”[18] While merely a glimpse into one part of just one feast, the description corroborates the claim that hosts would use food to flex their ability to bend nature and control the elements. As explained by the research of John D’Arms, “our surviving texts demonstrate that sows’ udders ranked along with fresh shellfish and mullet, and other major delicacies, at convivia where a host was seeking to convince his guests that he and his cook had taken elaborate pains and had spared no expense in constructing the menu.”[19]

The food served was elaborate, expensive, and often seen as exotic. For clients who often could not afford a dinner of their own, experiencing a multiple course meal with spices and ingredients sourced from around the Mediterranean was a riveting experience. Coupled with the choreographed and coordinated dinner entertainment from servants of the household, the client was shown why they should remain with their patron and continue lending support. If a patron could secure an entire boar and plentiful birds for one meal, they would be able to provide for the needs of the client. For local leaders seeking more power and prestige, the cost of acquiring elaborate foods and spices were justified by the guarantee of fealty they incurred. Furthermore, the chance to impress a higher-status guest rendered the expense completely necessary in securing a possible ally.[20]

PUBLIC FEASTING

Those who succeeded in securing a high-status ally were sometimes presented with an opportunity to eat in a public banquet. As Dunbabin explains, “Large numbers of inscriptions from all over the Roman world, and especially from central Italy, record the custom whereby wealthy members of the elite donated a banquet or feast …to members of their community. The recipients are most often the decurions, the city council, or the Augustales.”[21] These feasts, often put on to celebrate victories, religious ceremonies, or to honor an Emperor,[22] were events of mass spectacle and conspicuous consumption. This can be seen in the depiction below of one of the only preserved representations of a public banquet.

A relief of the Vestal Virgins showing the invited banquet guests seated in plain sight with a crowd gathered behind them. There is also a table shared by the guests and signifying clothing of their status.

Crowds would often gather around and watch the seated guests, learning about their elites in doing so. A banquet host with enough resources would even provide food for the general population, not just the seated guests.[23] This allowed them to gain the trust and favor of the masses as people would be provided with lavish food only seen at the nicest of private dinners.

In a way, this banquet was often the private dinner for those who would normally be in the dinner’s most respected roles. Explained by D’Arms, this edible, political tournament of champions would be used by the Emperor to showcase those in his favor while creating unity between different groups of elites as well as the citizen class. He notes, “The ceremonial epiphany of the Emperor validates the ranks and statuses of all the other diners, reinforcing visually the distinctive ties which linked together and integrated the disparate elements of the Roman social fabric.”[24] To be sat near the Emperor or even participating in the same banquet was an opportunity to rapidly accelerate one’s political prospects. Aspiring politicians of the Roman world relied on connections and word of mouth to grow their resources and garner support. Those who contributed to these feasts would be commemorated with inscriptions and statues further lending to their influence.[25] With the Emperor’s seating-based endorsement, it would prove an incredibly useful springboard to begin these conversations in full view of the public.[26]

CONCLUSION

Compared with private dinners, public banquets operated differently. Whereas private dinners were in a secluded setting, utilized a triclinium arrangement, and the participants were immersed in a carefully constructed world of art and sculptures, the public feasts were in view of the masses, often had many tables together, and focused on the display of food and wealth, not mystery and culture. Private dinners gave the host complete control over the evening’s conversation and order of events. Scenes like those of Trimalchio’s dinner might have been based in the reality that the host would use the meal to showcase their wealth, connections, and knowledge of history, mythology, and the world. They selected the art, helped design the menu, and would lead discussions. Meanwhile, public banquets were seen more as meals of peers in which the seated guests would discuss events and exchange information, aware that the public was viewing them and often hearing them. The host was more of a symbolic sponsor than a facilitator of discussion.

While the differences between public and private meals were many, they both achieved the same ends: (1) to allow those in power to flaunt their access to people and food resources, and (2) to provide a space in which deals could be made and political moves could be played. With food as a guise to lure elites and citizens alike to the table, the meal became a place of much more than just eating—it was one of meeting and dealing. By picking up the check, the host garnered dependency and loyalty from those below their social class and accrued respect and reciprocity from those at or above their status. This was how free food, offered in private dinners and public feasts, influenced the politics of Roman society.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bagnani, G. 1954. “The House of Trimalchio.” American Journal of Philology 75: 16-39.

Beard, M. 2007. The Roman Triumph. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bowie, E. L. 1986. “Early Greek Elegy, Symposium, and Public Festival.” Journal of Hellenic Studies 106: 13-35.

D’Arms, J. H. 1984. “Control, Companionship, and Clientela: Some Social Functions of the Roman Communal Meal.” Echos du monde classique 28: 327-348.

D’Arms, J. 1990. “The Roman Convivium and the Idea of Equality.” In Sympotica: A Symposium on the Symposion, edited by O. Murray, 308-326. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

D’Arms, J. H. 1999. “Performing Culture: Roman Spectacle and the Banquets of the Powerful.” The Art of Ancient Spectacle. Studies in the History of Art 56: 301-319. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art.

D’Arms, J. H. 2004. “The Culinary Reality of Roman Upper-Class Convivia: Integrating Texts and Images.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 60, no. 3: 428-50.

Dietler, M. 1995. “Feast and Commensal Politics in the Political Economy: Food, Power, and Status in Prehistoric Europe.” In Food and the Status Quest: An Interdisciplinary Perspective, edited by M. Dietler and B. Hayden, 65-114. Washington DC: Smithsonian.

Dietler, M. 2001. “Theorizing the Feast: Rituals of Consumption, Commensal Politics and Power in African Contexts.” In Feasts: Archaeological and Ethnographic Perspectives on Food, Politics, and Power, edited by M. Dietler and B. Hayden, 65-114. Washington, DC: Smithsonian.

Donahue, J. F. 2003. “Toward a Typology of Roman Public Feasting.” The American Journal of Philology 124, no. 3: 423-41.

Donahue, J. F. 2017. The Roman Community at Table During the Principate, New and Expanded Edition. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Dunbabin, K. 2003. “Public Dining.” In The Roman Banquet: Images of Conviviality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Faraone, C. A. 2006. Prostitutes and Courtesans in the Ancient World. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Garnsey, P. 1976. “Peasants in Ancient Roman Society.” The Journal of Peasant Studies, no. 3: 221-235.

Garnsey, P. 1999. “Haves and Havenots.” In Food and Society in Classical Antiquity, 113-127. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Garnsey, P. 1999. “You Are With Whom You Eat.” In Food and Society in Classical Antiquity, 128-138. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goddard, J. 1994. “The Tyrant at the Table.” In Reflections of Nero: Culture, History and Representation, edited by J. Elsner and J. Masters, 67-82. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Hammer, D. 2004. “Ideology, the Symposium, and Archaic Politics.” The American Journal of Philology 125, no. 4: 479-512.

Hayden, B. 2001. “Fabulous Feasts: A Prolegomenon to the Importance of Feasting.” In Feasts: Archaeological and Ethnographic Perspectives on Food, Politics, and Power, edited by M. Dietler and B. Hayden, 23-64. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press.

Hitch, S. 2016. “Sacrifice.” In A Companion to Food in the Ancient World, edited by John Wilkins and Robin Nadeau, 337-346. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Jones, C. P. 1991. “Dinner Theater.” In Dining in a Classical Context, ed. W. Slater, 185-198. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Kistler, E. 2017. “Feasts, Wine and Society, Eighth-Sixth Centuries BCE.” In Etruscology, edited by A. Naso, 195-206. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Lomas, K. and Cornell, T. J. 2003. Bread and Circuses: Euergetism and Municipal Patronage in Roman Italy. New York: Routledge.

Miller, J. 2016. “Euergetism, Agonism, and Democracy: The Hortatory Intention in Late Classical and Early Hellenistic Athenian Honorific Decrees.” Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens 85, no. 2: 385-435.

Murray, O. 1983. The Symposion: Drinking Greek Style. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Veyne, P. 1976. Bread and Circuses: Historical Sociology and Political Pluralism. Translated by B. Pearce. London: Penguin.

Wilkins, J. and Hill, S. 2006. “The Social Context of Eating.” In Food in the Ancient World, 41-78. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Woolf, G. 1990. “Food, Poverty and Patronage: The Significance of the Epigraphy of the Roman Alimentary Schemes in Early Imperial Italy.” PBSR 58: 198-228.

-

Garnsey 1976, 224. ↑

-

Garnsey 1976, 223. ↑

-

Dunbabin 2003, 72. ↑

-

Garnsey 1999. ↑

-

Woolf 1990. ↑

-

Woolf 1990, 212. ↑

-

Faas 1994, 39. ↑

-

Faas 1994, 38. ↑

-

Faas 1994. ↑

-

Faas 1994, 43. ↑

-

Garnsey 1999, 130. ↑

-

Wilkins and Hill 2008, 40 ↑

-

Dunbabin 2003, 43 ↑

-

Dunbabin 2003, 43 ↑

-

Dunbabin 2003, 40. ↑

-

Clarke 1991, 203. ↑

-

Clarke 1991, 203. ↑

-

Jones 1991, 186 ↑

-

D’Arms 2004, 434 ↑

-

D’Arms 2004. ↑

-

Dunbabin 2003, 78. ↑

-

Dunbabin 2003. ↑

-

Dunbabin 2003, 72. ↑

-

D’Arms 1990, 311. ↑

-

Dunbabin 2003, 98. ↑

-

Garnsey 1999, 135. ↑